persian rugs

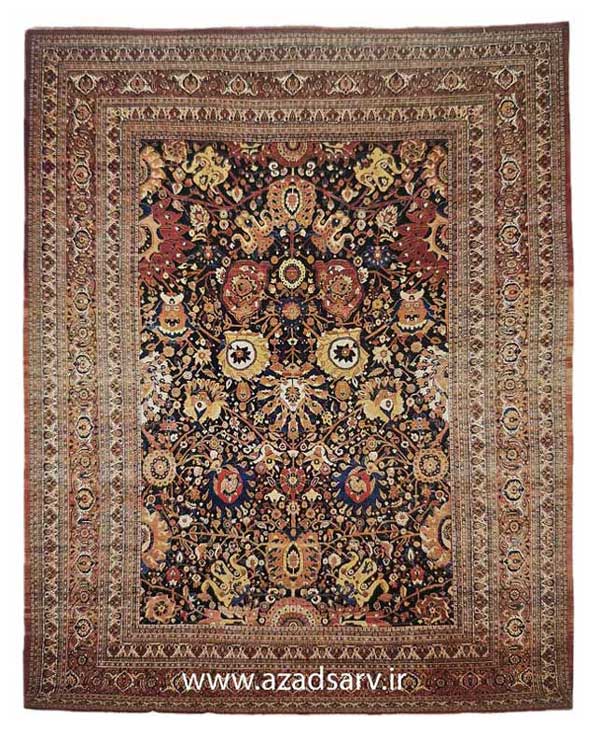

There is some confusion over the word Persian as it refers to oriental rugs. The country known as Persia changed its name to Iran in the 1920s, but by that time the term Persian rug`had become something of a generic name for any hand-made pile rug from the Near East. Rugs from Iran are still often referred to as Persian, and in this book both terms will be used. Iran serves as a good example of the differences between city rugs and those made by villagers and nomads. While rugs were woven there for at least several millennia, apparently only fragments dating before ۱۵۰۰ survive, although this is a matter of controversy. Rugs _ are often extremely difficult to date, although three dated carpets from the Safavid dynasty (1500-1721) bear woven inscribed dates, including the pair of carpets found at the Shrine of Ardabil with a date of ۱۵۳۹/۴۰. The most complete of these carpets is currently in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, while another early Persian carpet, inscribed with the date most plausibly read as ۱۵۲۲/۲۳ is in the Poldi Pezzoli Museum in Milan. Other carpets surviving from the early Safavid period include three large silk carpets of an extremely fine weave, with two of them ranging around ۷۰۰ asymmetrical knots per square inch. These carpets. which include large examples in Vienna and Boston, are plausibly dated stylistically to the early sixteenth century and associated with the Safavid court of Shah Ismail or Shah Tahmasp.

While hundreds of carpets survive from the Safavid era, there is still controversy as to where many of them were made. Tabriz, the first Safavid capital, was almost certainly a source, while the subsequent capital in Isfahan is known to be a source. European travellers of the seventeenth century describe the exact location of

the carpet workshops, and there is documentation of carpet weaving in Kashan at about the same time Kerman was also a major source of carpets in a wide variety of designs, including a type characterised by realistically drawn blossoms in a lattice framework in which vases may be found. There is also good reason to believe that carpets were woven in Herat, which was part of the Persian Empire during Safavid times. After the Safavid collapse, there seems to have been a decline in rug production, although it certainly continued for local use. Safavid designs had became part of an enduring design lexicon that has lasted up to the present, with elaborate, stylised palmettes, scrolling vinework, complex medallions, and multiple lattice systems. Many of these same motifs resurfaced in the nineteenth century when the country began again to produce rugs in quantity to meet international demand.

PERSIAN CITY RUGS

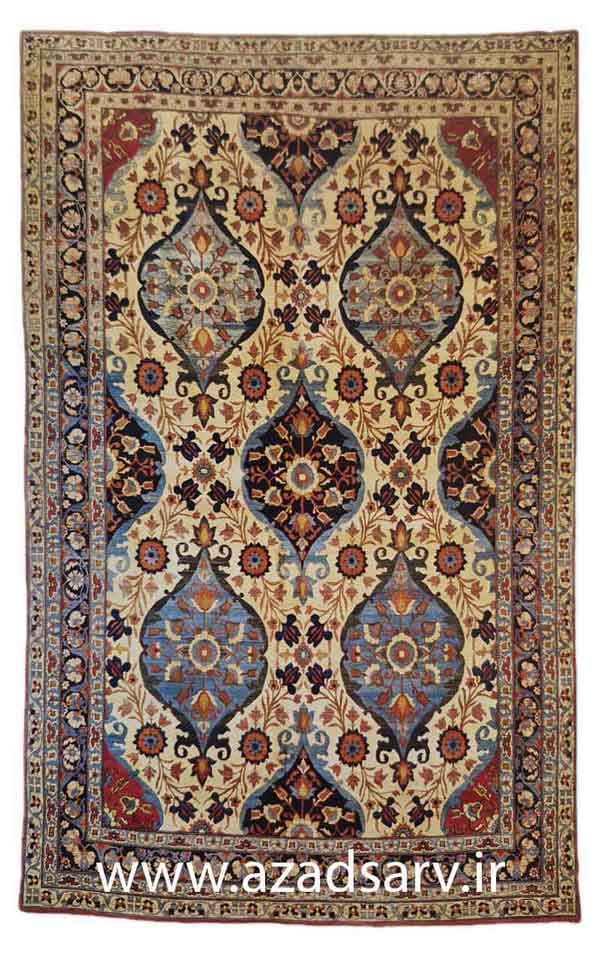

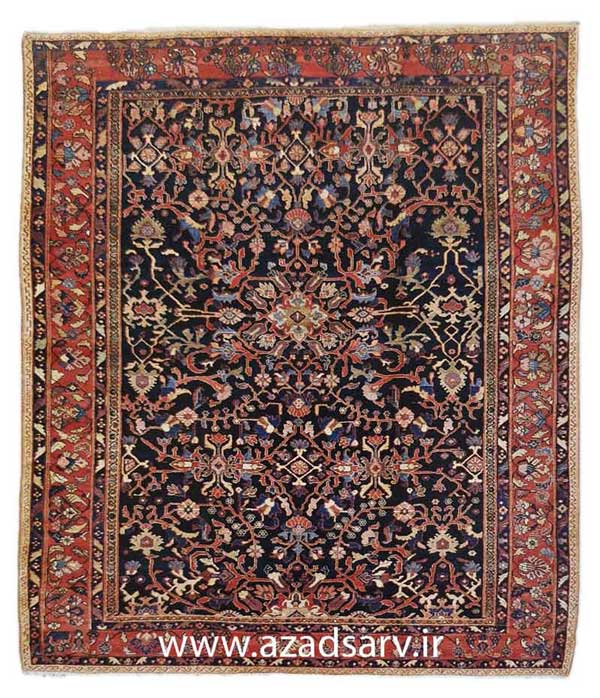

Persian city rugs havea number of features incommon, including use of the asymmetrical knot on a cotton foundation in which the wefts usually cross twice between the rows of knots. They are finely woven, ranging from about ۱۱۰ to over ۶۰۰ knots per square inch, and their designs are ordinarily curvilinear and floral, with motifs adapted from rugs of the Safavid period. They are typically designed by specialists, with ool processed by professional dyers. Weaving today is carried out by young women and children, though in the Safavid period men were also employed. Most city rugs are double-warped which makes them rather inflexible (Figure 1). Basic designs of the Persian city rug are widely copied from China to the Balkans, India and Pakistan in particular have been borrowers of Persian designs.

Tabriz

Merchants from Tabriz took the lead in organising the rug industry in Iran when it revived in the last half of the nineteenth century, for Tabriz lies relatively close to Istanbul, the major shipping point to Europe. As demand from the West grew, these dealers first organised a system by which old rugs from the bazaars were channelled to Tabriz for subsequent shipment abroad. When the supplies of old rugs proved insufficient for the demand, these same merchants were instrumental in other parts of Persia in encouraging the expansion of local rug industries.

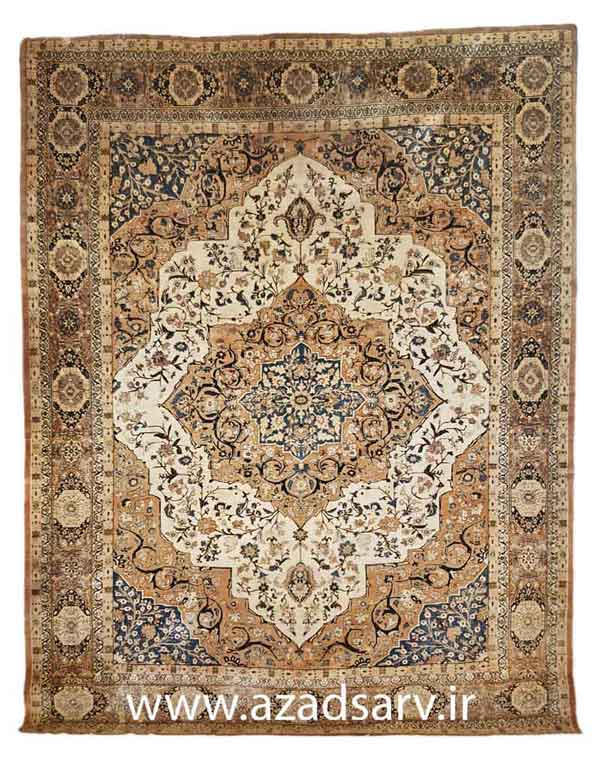

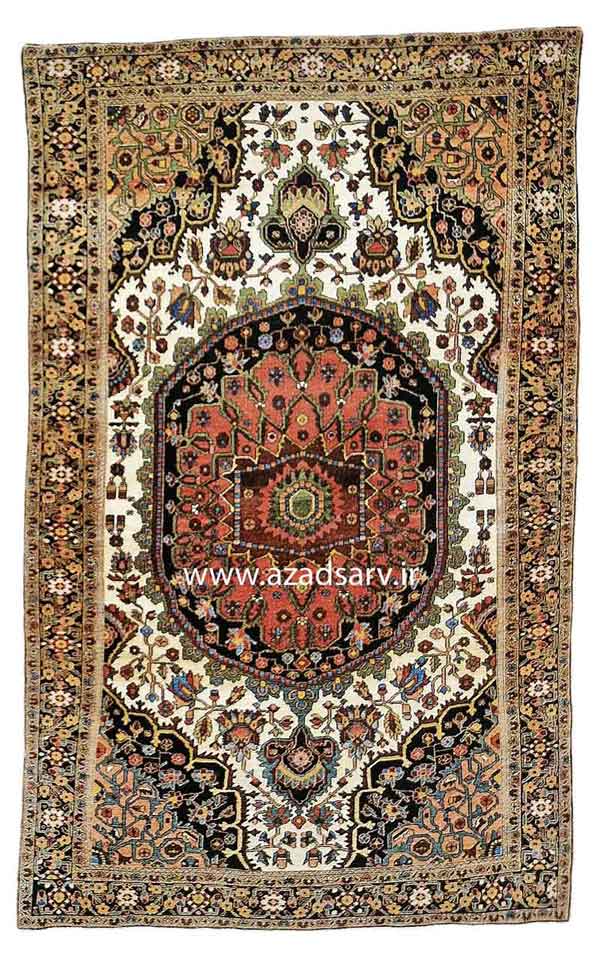

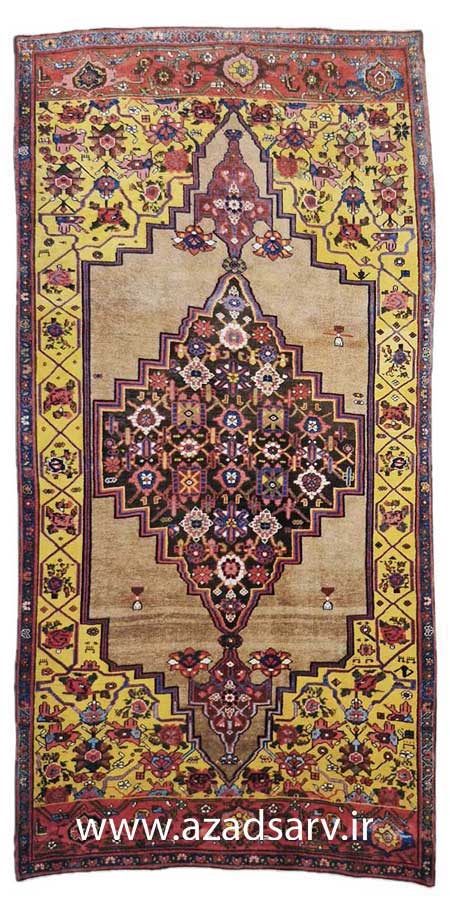

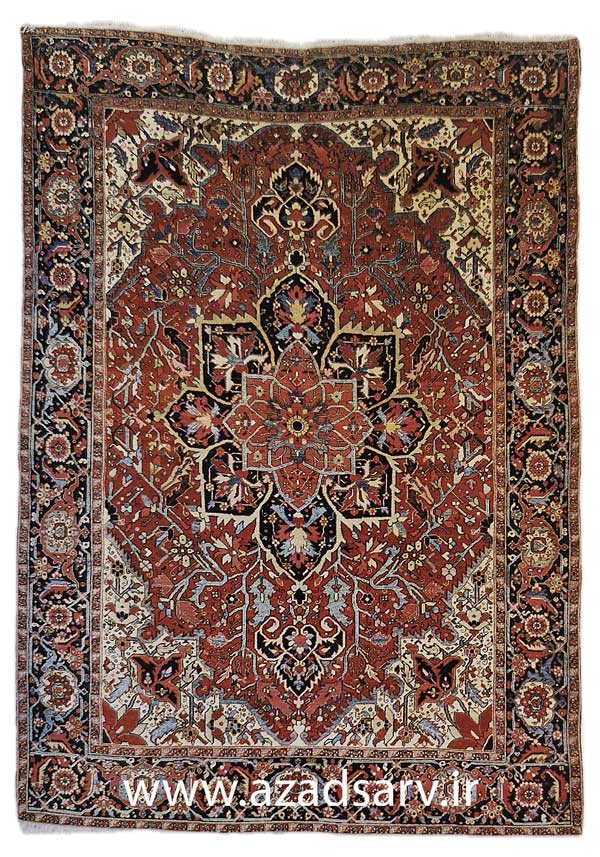

While there had been a low level of rug production in the Tabriz area, possibly extending centuries into the past, the new demand also brought about an expansion of the local industry which began to produce a type of rug that became recognisable throughout the western world. The Tabriz carpet followed the tradition of using cotton for the warp and weft, while the pile wool has a rather harsh feel. The designs most frequently included medallions and often showed adaptations of Safavid motifs (Figure 2).

These carpets differ from other Persian city carpets in being woven with the symmetrical knot

From the first decades of the revival, the workshops in Tabriz have been adept at modelling their carpets to meet western demands, changing the colour schemes and designs as needed to gain market advantage. There are many grades of Tabriz carpet including some of the finest and some of the coarsest city types.

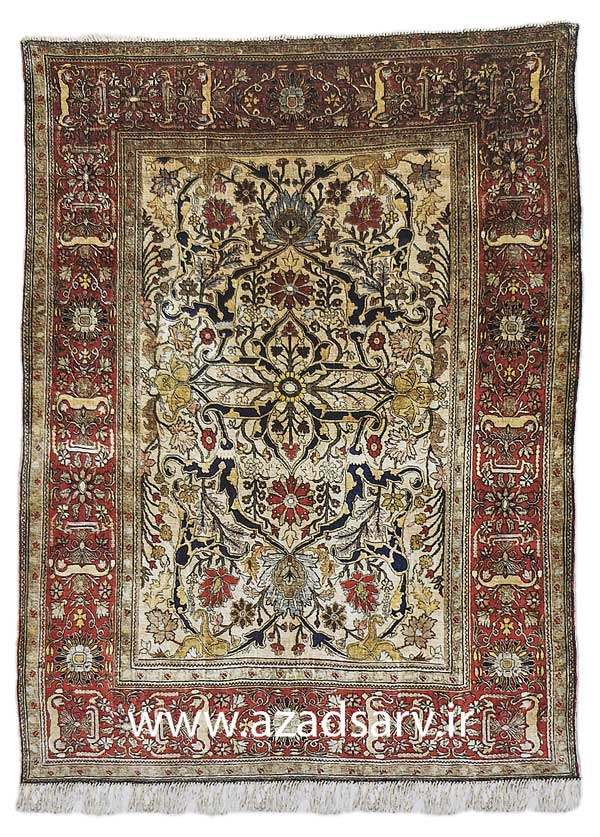

A group of silk rugs from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was woven in Tabriz, and one occasionally sees examples at auction going for steep prices. The designs were often borrowed, at times from early Turkish prayer rugs.

Kashan and Qum

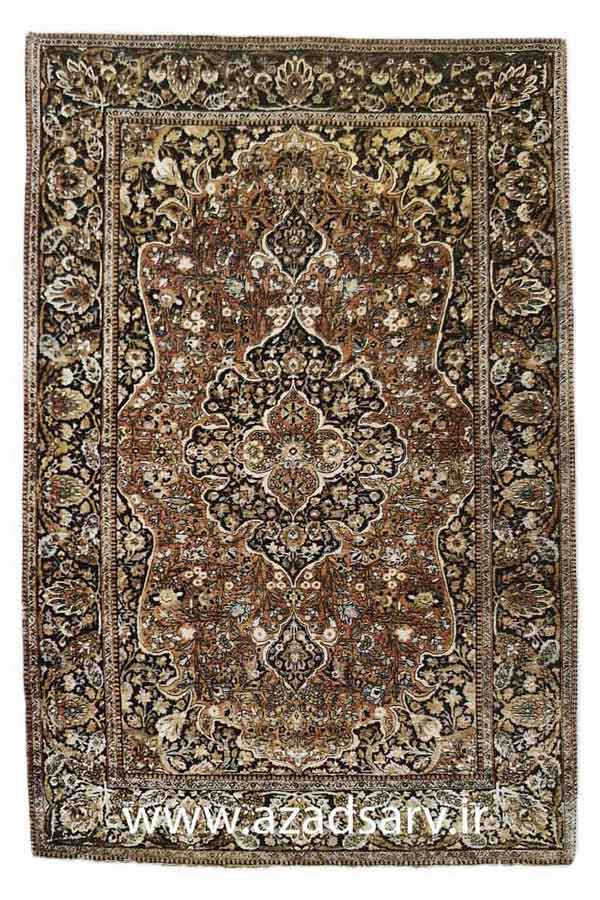

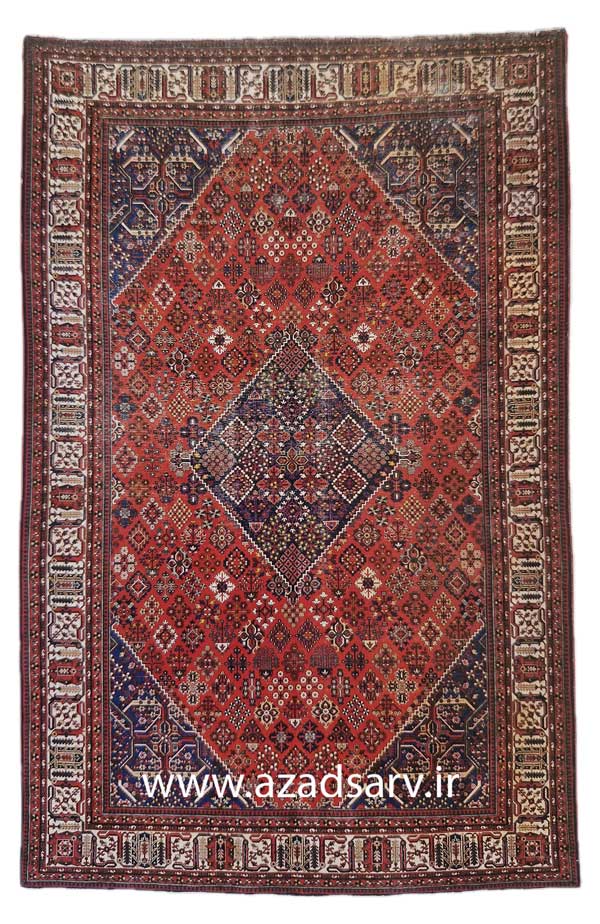

The cities of Kashan and Qum are often discussed together, as their rugs share the typical structure of the Persian city rug, and their designs are similar. While weaving in Kashan is documented during Safavid times, it is unclear whether there has been an unbroken tradition. Kashan rugs from the last half of the nineteenth century are known, usually in medallion designs (Figure 3).

By the end of the nineteenth century Kashan rugs were among the most consistently finely knotted of all Persian rugs, and it was only half a century later that the rugs of Isfahan and Nain came to exceed them in the number of knots per square inch

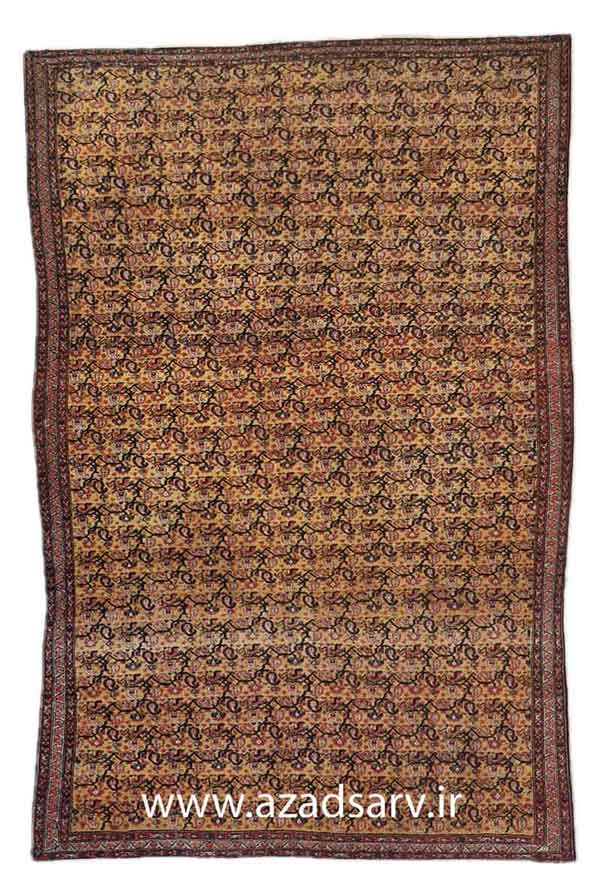

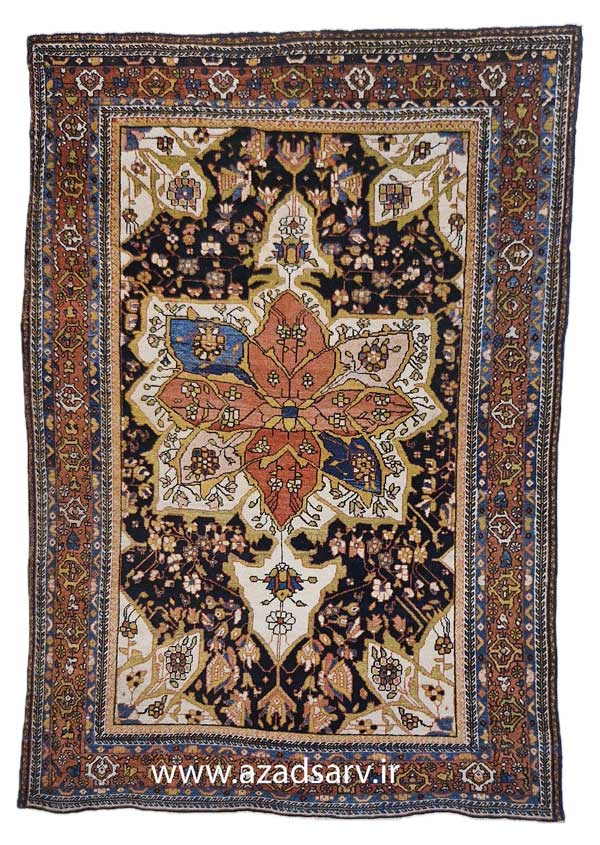

Silk has long been produced in the Kashan area, and number of early Kashans were all silk. A late a nineteenth/early twentieth century type of Kashan was made with merino wool from Australia or New Zealand, spun in England, and these rugs are described as having ‘Manchester wool (Figure 4).

Later Kashans have a wool indistinguishable from that of other Persian city rugs.

Medallion designs have remained common on Kashan rugs, often on a red field with relatively small lozenge-shaped medallions. Prayer rug designs are also encountered, and occasionally one encounters a pictorial Kashan. Kashans of the last several decades often show a colour scheme based around ivory, blue, and beige.

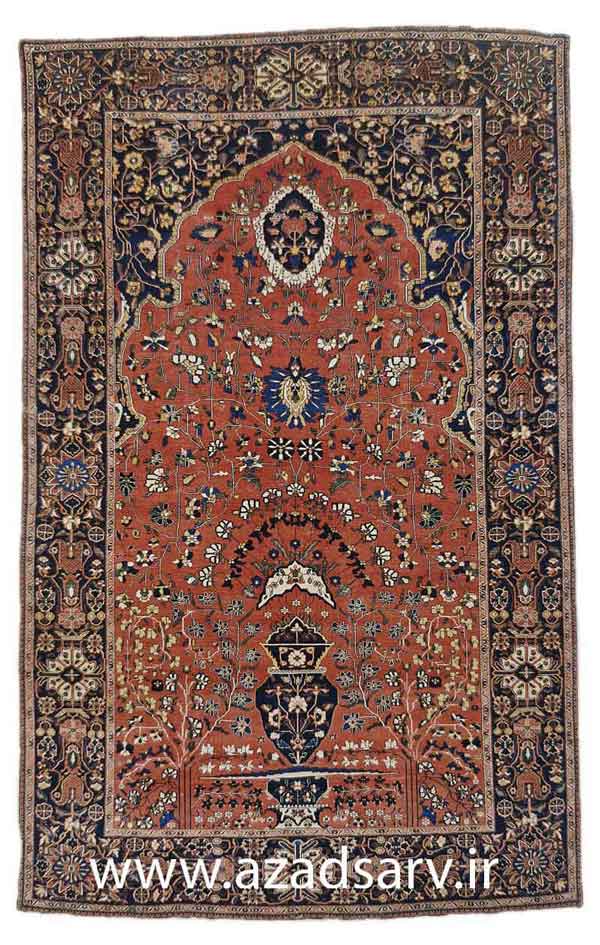

The industry in Qum has mirrored that of nearby Kashan, although modern production appears to have begun several decades later, and there was no tradition of rug weaving there during Safavid times. Many of the smaller pieces are in prayer rug designs, while a number of Qum silks appear in a so-called garden design in which the field is divided into squarish compartments, each with a variety of floral figures.

Both Kashan and Qum rugs range from about ۱۴۰ to over ۳۰۰ knots per square inch, with the silk pieces often being finer. Both types enjoy high status in local and western markets.

There are several towns near Kashan, most prominently Aroon, that weave Kashan designs in a slightly lower grade

Isfahan and Nain

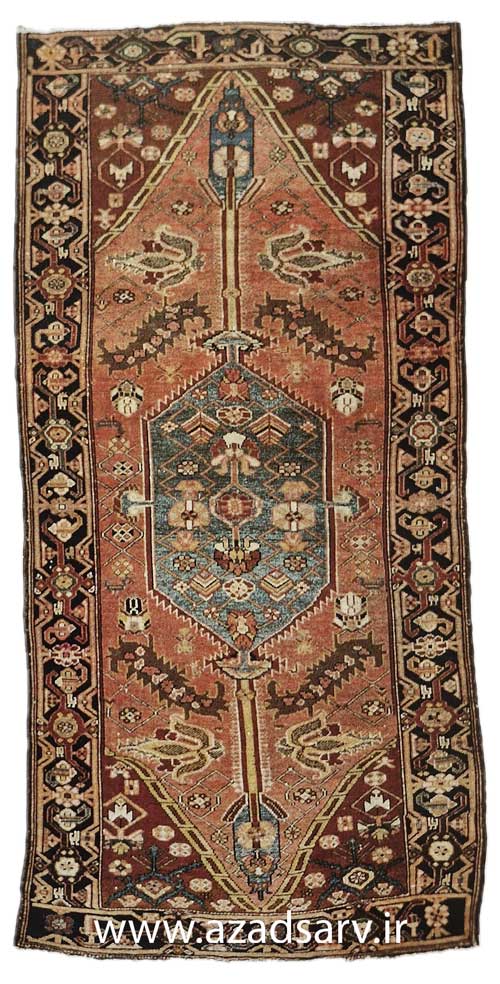

While Isfahan was a producer of rugs for the Safavid court in the seventeenth century, the art seems to have died out there until it was revived in the first quarter of the twentieth century. The Isfahan is among the finer Persian city rugs, ranging between about ۲۵۰ to above ۶۰۰ asymmetrical knots per square inch. Finely woven rugs may have a silk foundation, and a number of them have an inwoven signature of the master weaver, often in a small patch of pile weave at one end, Silk Isfahans also often show hunting scenes Medallions are common, often on a red field, although there are also intricate repeating designs (Figure 5)

In many respects Isfahan represents the centre of Safavid art, with many surviving mosques and several palaces associated with the lavish imperial court of the seventeenth century. With such inspiration locally accessible, it is not surprising that these early designs have been particularly prominent on Isfahan rugs. A lower grade rug, resembling the Isfahan and also usually in medallion designs, is made in the town of Najafabad.

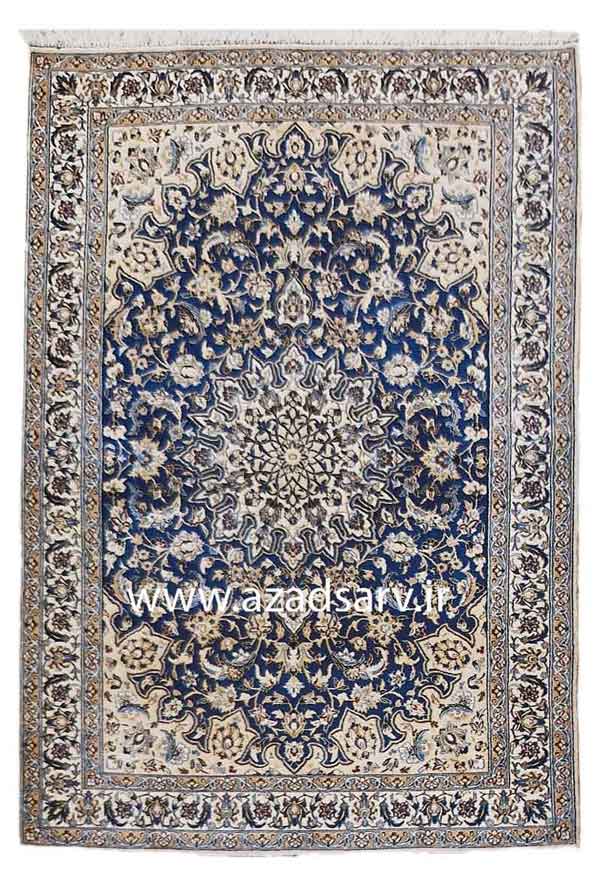

The rugs of Nain resemble those of Isfahan, although weaving may not have begun there until the ۱۹۴۰ s. Nains average an even higher knot count than Isfahans, and they frequently have the outlines of floral figures woven in ivory silk, giving additional highlights to the rug. Later Nains often have a colour scheme based around ivory, blue, and beige, with less red than the typical Isfahan (Figure 6).

Kerman

The Kerman rug has an unusual structure. There are three wefts between the TOWs of knots, with two of them pulled tightly to place the warps on two levels. Most rugs of the Safavid period from various parts of the country were woven in this manner, but, interestingly, the feature survives among asymmetric- ally knotted rugs only in Kerman.

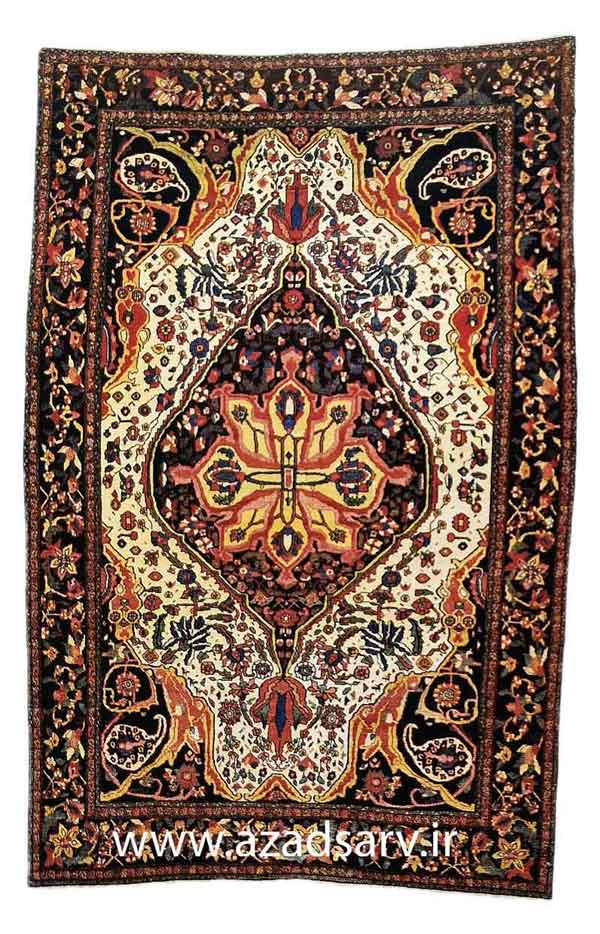

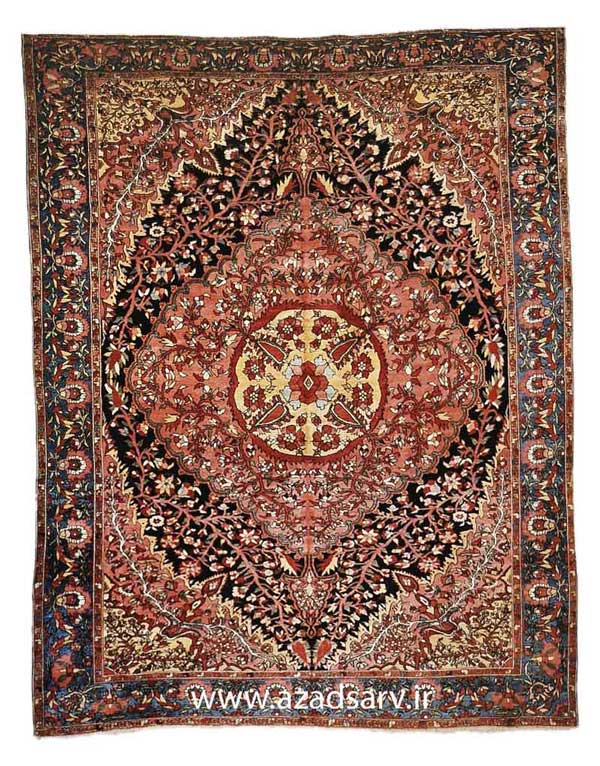

The rugs of Kerman are noted for excellent wool, which makes for a bright white rather than the usual darker ivory. Red colours were long based on insect dyes, a characteristic shared only with the rugs of Mashhad and other cities of Khurasan. Kermans show an enormous variability in design, as designers are artisans of substantial status there. Foreign firms gained control of many Kerman looms late in the nineteenth entury, and most of the rugs were consequently directed toward western markets. particularly American. These included a number of rugs of unusual size, and when one finds an early twentieth century rug over 18 feet (5.5 metres) long it is likely to be a Kerman. Medallion designs have been most common with elaborate floral motifs covering the field (Figure 7).

The standard Kerman weave remained in the vicinity of about ۱۴۰ knots per square inch for decades, although there have always been finer pieces ranging to over ۳۰۰ knots per inch.

By the second quarter of the twentieth century these rugs seemed to lose something of their Persian character, as the pile was made longer and the designs simpler. As the mid-twentieth century approached, open fields with attenuated pastel colours and French style broken borders became increasingly common. During the last several decades the Kerman rug has reverted to earlier traditions to appeal to the local Iranian market. The colours are brighter, and the designs follow those of earlier rugs (Figures 8 and 9).

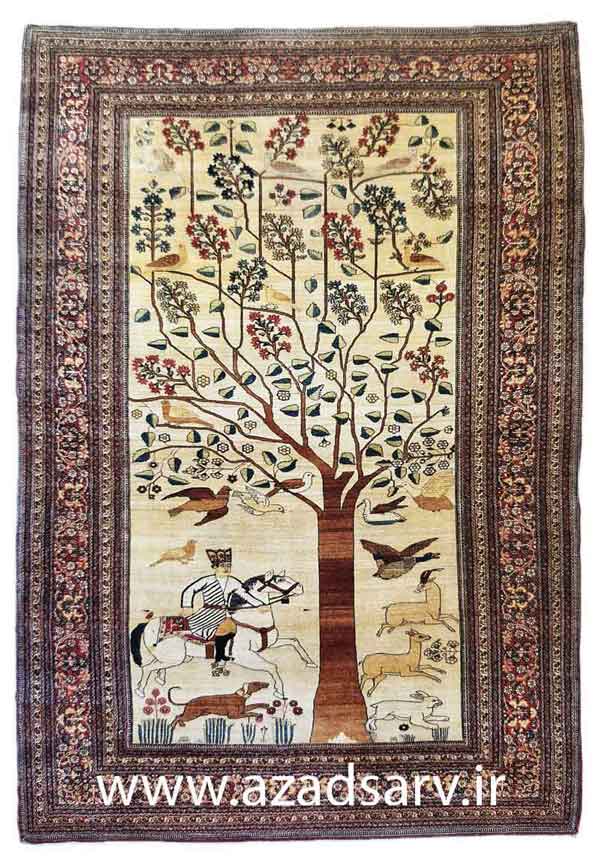

A number of pictorial Kermans are known, along with pieces in prayer rug designs, usually with a central tree and at times with animal and bird figures.

All sizes are woven from small mats to giant rugs Several other cities in the vicinity of Kerman have long

produced a similar type of rug that is usually sold in the West under the Kerman label. The ancient city of Yazd, on the edge of the Great Desert, has a long tradition of rug weaving. Its products resemble the Kerman, although regional output has not been so consistently directed toward western markets. Mahan and Ravar also have produced Kerman-type rugs, and at times the most finely woven Kermans are given a Ravar label.

Mashhad, Birjand and Qain

Like the Kerman, which they often outwardly resemble, these types have cooler reds from insect dyes, although they have a structural peculiarity that sets them apart. Here the jufti asymmetrical knot is endemic, and the rugs, which are woven with a particularly soft wool from the area, are less durable than most other Persian city rugs. As the jufti involves tying the asymmetrical knot over four warps rather than two. the resulting fabric is less resistant to wear. Medallion designs are particularly common, although many nineteenth century examples show repeating designs.

Rugs from Mashhad are also unusual in that the region produces rugs with asymmetrical jufti knots along with symmetrically knotted types. The latter tradition probably began with Tabrizi merchants in the late nineteenth century, when they established a

weaving industry in Mashhad modelled on that of Tabriz. Rugs of both types may show the designs, including many prayer rugs and pictorial same carpets (Figure 10).

Several workshops in Mashhad became particularly well known during the first quarter of the twentieth century, and -although their output was limited some of their rugs were extremely finely woven with complex floral designs.

Rugs from the Birjand and Qain areas are consistently asymmetrically jufti knotted, tradition- ally using red shades based around lac or cochineal, and it is often difficult to tell recent examples apart (Figure 11).

During the late nineteenth century, however. each of these areas, as well as the town of Doruksh, produced a distinct type of rug. Floral repeating designs were popular, but medallion designs are now most common, often in standard room sizes. Quality is variable from relatively coarse to extremely fine. Nowhere is this better exemplified than in the town of Mud, near Birjand. Here a medium grade medallion rug has been produced in great numbers, and these often appear in the West. Much less common is a small group of extremely fine, well- designed .Mud rugs

Arak

The area around Arak (formerly Sultanabad) has woven something of a hybrid between the Persian city rug and village rugs. Most of the production is from surrounding towns and villages, and the rugs range from fine to medium density, with the asymmetrical knot on cotton foundations. They may show elaborate curvilinear designs, although not usually involving Safavid motifs Many rugs from the last half of the nineteenth century have survived, and many of these pieces fron he Arak area show designs with rather stiff medallions. These were usually labelled as Sarouks although such pieces were woven in many places other than the town of that name (Figure 38).

Another type of rug from the district was sold in the West under the Ferahan label, and these typically had repeating designs, often the herati. Most had a blue ground colour and an appealing light green colour in the border.

Early in the twentieth century, many rugs from this area were made under the direction of foreign firms. and the output was directed towards the West. These pieces were carefully designed from traditional Persian motifs, using colours suited to western tastes, and avoiding the bright reds favoured in Iran. The rugs were usually marketed under names reflecting their grade rather than a specific town or village of origin.

Sarouk was the name given to the highest grade, whether the particular carpet was woven in the town of that name or a number of other places that produced the same kind of carpet. Unlike the turn-of- the century Sarouk, with its rather stiff medallion design of a type probably adapted from early Tabriz carpets, the field was usually covered with detached floral sprays, usually on a red ground. It was tightly woven and ranged from about 100 to 200 knots per square inch (Figures 13 and 14).

The Sarouk was popular in the United States during the 1920 s and ۱۹۳۰ s. Before they were sold, these rugs were often bleached and the reds repainted with a maroon dye, giving them a darker appearance. They are thus unusual in showing a darker red colour on the front than on the back. One would expect the exact opposite, as it is usually the front surface of the rug that fades, but in these cases, the colour painted on to the surface was usually darker than the original red. Mahal is usually used as a label for lower grades from the Arak district. Most were woven under controlled conditions and are of good quality. although they are not finely knotted. Colours are usually excellent, with little abrash. They are based around classic Persian patterns with elements created specifically for western markets (Figure 15). At times these rugs are sold under the Ziegler label, from a major foreign-owned firm in Arak that controlled many looms and was a major exporter to Europe.

IRANIAN TOWN AND VILLAGE RUGS

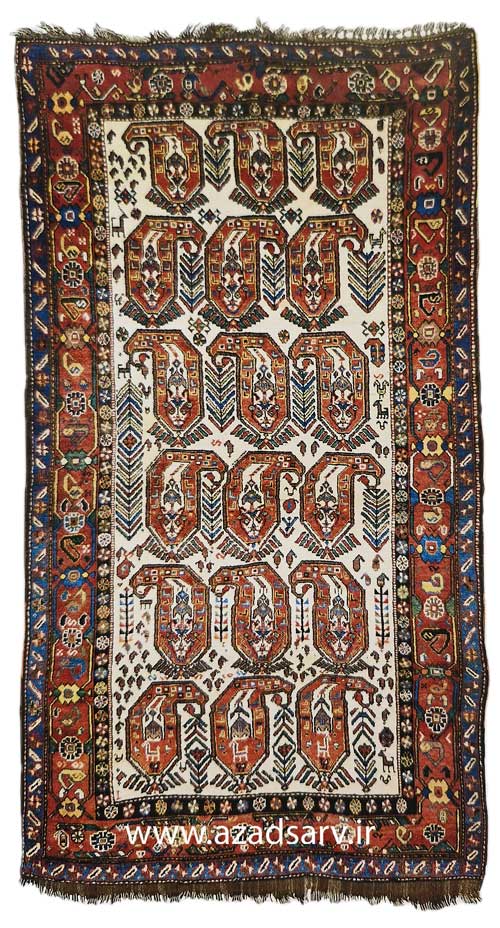

There is a group of rugs made in the countryside in Iran by villagers who either raise sheep or purchase their wool from neighbouring nomadic groups. Their rugs resemble neither the city rugs nor are they like the rugs woven by nomads. Examples from the nineteenth century are usually woven on an all-wool foundation, as this was available from local production.Cotton has come into wider use in the last century, and the knotting may be either symmetrical or asymmetrical, most often the former, and the rugs are woven in a variety of shapes and sizes. For the most part, however, the largest room-sized rugs are woven in Iranian cities.

The Kurds in particular have produced a wide range of village rugs, although the finest Kurdish rugs, from the city of Senneh (now called Sanandaj) are something of a hybrid between city and village (Figure 16).

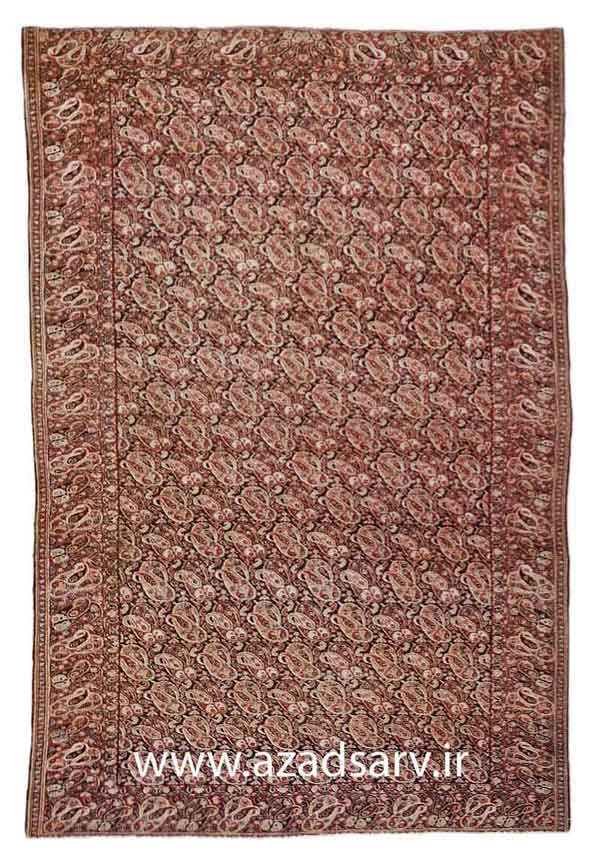

They may have extremely short pile, fine weave, and cotton foundation with only one weft shoot between the rows of knots. Although some of the older rug books describe the asymmetrical knot as a Senneh knot, the rugs from this city are symmetrically knotted. Designs of the Senneh include fine renditions of the herati and repeating boteh figures. There are some medallion designs, which are far less curvilinear than the standard Persian city rug. The finest Sennehs may have silk warps, at times in bands of different colours. It is likely that rugs were woven in Senneh well before the late nineteenth century expansion of rug weaving,as some examples with early inscribed dates are known.

A group of villages around the Kurdish town of Bijar weave an entirely different type of rug known for its rigidity. These rugs often – but not always – have three thick wefts between the rows of knots, with alternate warps pushed into different levels making them double-warped. The range of designs includes the classic Persian herati, but there are also many medallion rugs, some with bold arabesque leaf designs

(Figures 17 and 18).

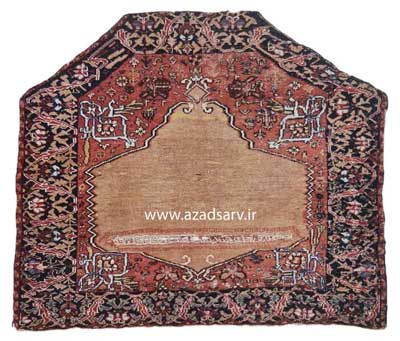

Figure 17. This small Bijar rug is shaped to cover a saddle, and like other Kurdish rugs from this area is particularly thick. While the Senneh is, for the most part woven within the city, the Bijar is woven in several dozen nearby villages and in the city of Bijar. Consequently there is much more variation in the designs and textures of the rugs.

These rugs are extremely durable and some are very large. A number of sampler’ rugs are known from Bijar, where they were apparently used as something analogous to pattern books. In a small rug the entire design lexicon of a larger rug could be represented, although these pieces often lacked design symmetry.

Hundreds of other Kurdish villages in western Iran also produce rugs of a more generic type, usually with wool foundations with a rather loose weave. The designs include those used by Senneh and Bijar, but the variation is somewhat greater. Many rugs show a repeat of simple geometric figures. A number of long narrow rugs, called runners in the West, are made in Kurdish villages. The wool of these rugs is ordinarily of an excellent quality (Figure 19).

A group of Kurds that were transplanted to an area in eastern Iran near the town of Quchan have continued to weave rugs, although_ they have evolved n different irections during the last several centuries (Figure 20). Some Quchan Kurd rugs are woven in designs adapted from the Turkmen, and another group has taken on Baluchi features, although the symmetrical knot has been retained. Although they were separated from the western Kurds in the seventeenth century, it is interesting to see that some of the rugs still show designs essentially identical to those of the western Kurds

Hamadan

The Hamadan area has probably supplied more rugs to the West during the last century than any other part of Iran, although they are

generally of rather coarse weave with generic Persian patterns. They are not made within the city of Hamadan itself, but in several hundred villages in the surrounding area. These rugs almost exclusively employ a structure that sets them apart from most other symmetrically knotted village rugs. They have only one weft between the rows of knots, and this may easily be seen from inspecting the back of the rug. Only the Bakhtiari types of the Chahar Mahal and a few rugs from the Heriz district have this characteristic. Very early Hamadans may have a wool foundation, but almost all examples from the last century have cotton (Figure 21).

Although the designs are taken from the standard Persian repertoire, with many pieces woven in crude variants of the herati or mina khani patterns, they show a wide range of variation on common motifs. A number of the rugs show botehs of different sizes, while others have repeating geometric figures. Most are in small sizes or in a runner format, and only a few places in the Hamadan district weave large rugs. Two parts of the district weave a finer than average grade than the typical Hamadan. The Malayer area produces a rug that is fine enough at times to be mistaken for a Senneh, which it often resembles in design. The Jozan area produces a finer symmetrically knotted rug that often resembles the earlier Sarouk in design, with which 1t also shares the use of two weft between the rows of knots. Jozan rugs are often more heavily abrashed than the Sarouk (Figure 22),

symmetrically knotted and often shows more abrash

The earliest generation of Hamadans to reach the West often had a camel-coloured field, and many of them were in a runner format. While these pieces are often described as woven of camel hair, this is not the case, as the wool has simply been dyed in a tan colour, often with walnut husks or gall nuts

Heriz

Heriz is the centre of a cluster of towns and villages to the east of Tabriz, where a popular type of medallion rug is woven. It is thick, coarsely knotted, and has been relatively inexpensive (Figure 23).

Few surviving examples are found in anything but larger sizes, from about x 10 and 9 x 12 feet (2.4 x 3 and X ۳ ۲.۷۵ x ۳.۶۵ metres) up to much larger examples While Hamadan supplied scatter sizes in the early twentieth century, the Heriz area was the major supplier of relatively inexpensive room-sized carpets.

Those with natural dyes that have survived in good condition, however, have become extremely expensive although reproductions of Heriz rugs with natural dyes have recently become common.

The rugs are symmetrically knotted and labelled not so much by place of origin, but by grade, although the grades are based upon village names. For the last century the finest grade has been described as a

Serapi, often with designs verging on the curvilinear. Finely woven rugs, now described as Ahar, are also somewhat curvilinear and may show an unusual

feature in which many of the stylised floral figures may be outlined in two colours rather than the usual single outline. The term Gorevan was formerly used for the lower grades, but it is less used now, and many are labelled simply as Heriz.

While most of the rugs have medallion designs, perhaps 10 per cent have overall designs of large stylised floral and leaf forms. For some reason the classic herati and boteh designs so common from other parts of Iran were seldom used in this area. Most of the rugs have two wefts between the rows of knots, but several villages use only one weft between the rows, including the town of Karadja, which is known for long narrow rugs. These rugs are generally attractive and durable. Colours early in the century were excellent, but later periods featured less attractive synthetic colours.

The town of Sarab in the southern part of the Heriz district is known for its long rugs with a limited range of designs on a camel-coloured field,

A group of silk rugs from the late nineteenth century are often given the label of Heriz, although most may have been woven within Tabriz (Figure 24)

The Chahar Mahal

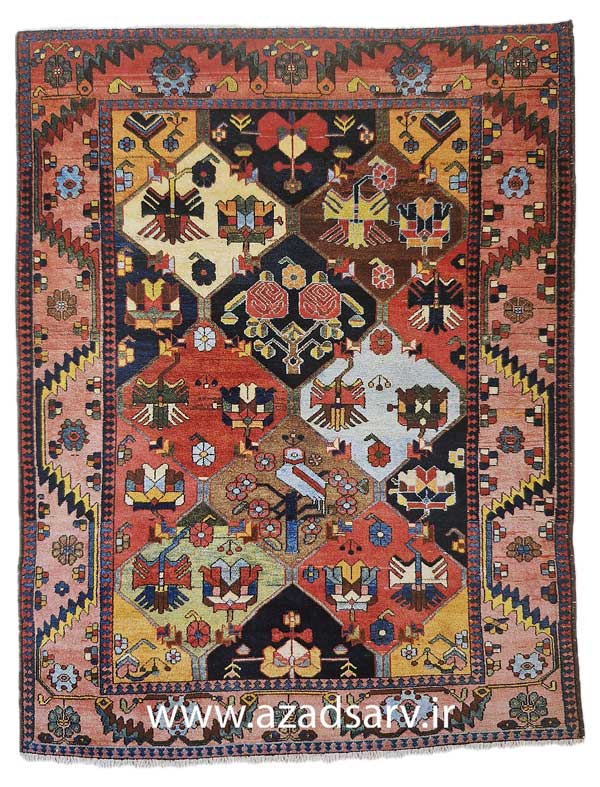

A group of villages in the Zagros foothills just west of Isfahan comprises a weaving area whose rugs are often labelled as Bakhtiari, although many weavers are Kurdish villagers. The rugs resemble the Hamadan in structure, with the use of only one weft between the rows of knots, but generally have darker colours, with more brown and dark green. Many examples are found with squarish or lozenge-shaped compartments within which are found stylised floral figures (Figure 25).

These rugs are thick and come in a wide range of sizes. The Bakhtiari also weave gabbeh rugs, a thick, coarse, symmetrically knotted fabric with simple geometric designs, and a wide variety of nomadic trappings (Figure 26). Recent Bakhtiari rugs have a cotton foundation, although there are surviving examples from an earlier generation woven on wool warps and wefts.

Other towns of note

The town of Joshaqan, south of Kashan, has a long tradition of making carpets. The rugs are of medium grade, asymmetrically knotted on a cotton foundation, and are characterised by designs with stylised floral sprays configured in a lozenge shape, at times with a small medallion. There has been little change in the traditional designs for over a century (Figure 53). Several other nearby towns have taken to weaving the classic design, some in a tighter weave, Occasionally one will find a rug in a Bakhtiari weave and a Joshaqan design

Liliyan

Although the Liliyan rug is woven in a number of villages, it resembles city rugs from the Arak region. During the mid-twentieth century rugs for the American market were woven here, often with dark maroon field colours and a design of detached floral sprays similar to the contemporary Sarouk The structure is distinctive in that the rugs are made with asymmetrical knots, but there is usually only one weft between the rows of knots. Most single wefted rugs are symmetrically knotted.

RUGS OF THE IRANIAN NOMADS

While the Iranian government, for much of the twentieth century, attempted to settle its population of nomads, there are a number of tribes still practising at least partial nomadism. This involves part of the tribe migrating to progressively higher ground in the spring and summer to find fresh pasturage for their flocks, and then returning to the lowlands for the cold season. Parts of each tribe remain sedentary, growing cereal crops for survival over the winter. Eventually this way of life will probably become extinct, as migrating nomads have always been problematic for governments. Nomads have been difficult to control, and their lifestyle has led to a certain independence from central authority. It also has led to rugs with a different visual flavour from those of the Persian villagers, and consequently nomadic rugs have held a special appeal for the collector. The large city of Shiraz in southern Iran is not a significant producer of rugs, but there are many weavers among the nomadic and village populations of the surrounding areas. In addition to the villagers, who are mostly of indigenous Iranian stock, there are two major tribal groups with their own leadership structures: the Qashqa’i and the Khamseh Federation. Year after year these groups have moved their flocks from the lowlands to higher ground as the summer progresses, and these moves have developed a certain complexity in which the same transit areas are often occupied by different tribes at different stages in their migrations. Then as the weather cools, and the tribes move toward their winter quarters, the same pattern of movement takes place. Over the centuries alliances and enmities have developed between the different tribal groups, and no doubt at times in the past there has been open conflict.

The Qashqa’i

The Qashqa’i, a grouping mostly of Turkic origin, and the dominant tribe of the region, is made up of a number of subtribes including the Qashguli, Bulli, Darashuri, Kuhi, and others. There are theories that the first of these Turkic people entered the Fars region in the thirteenth century, having been forced south by the arrival of Mongol armies in Azerbaijan. At times the Qashqa’i have represented a powerful force within Persia, as a migrating tribe is organised along military lines, with all men essentially able to function as warriors. There has also always been a certain friction,. and interdependence, between the migratory and settled populations

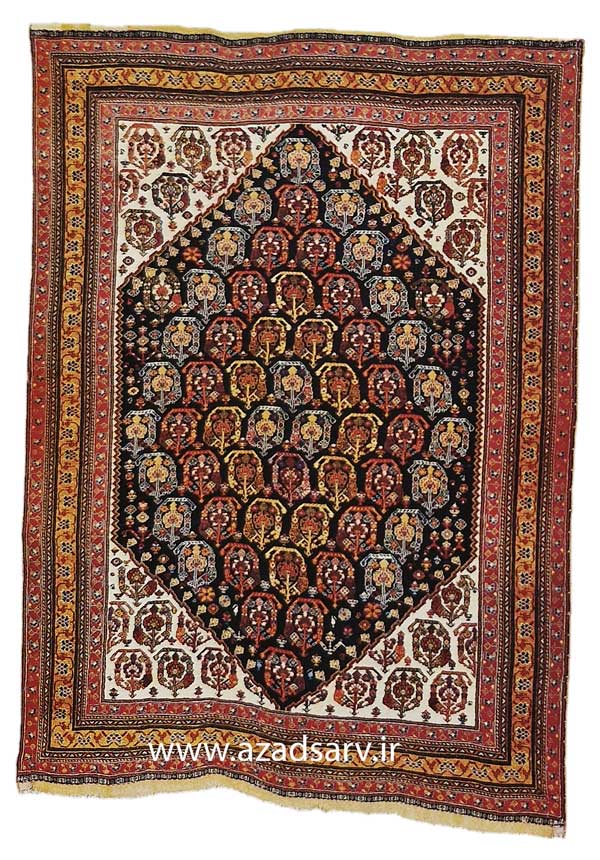

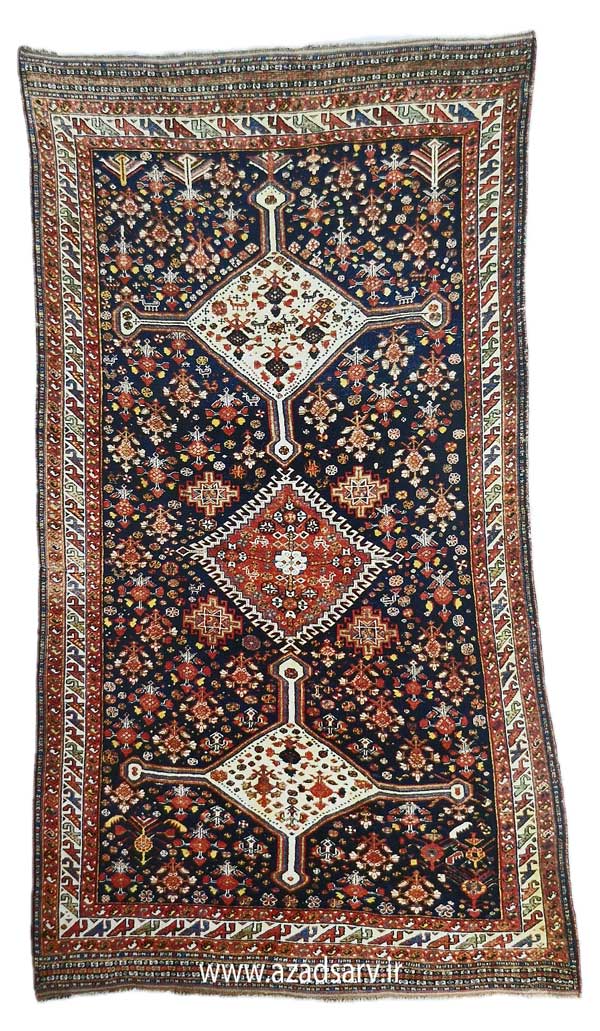

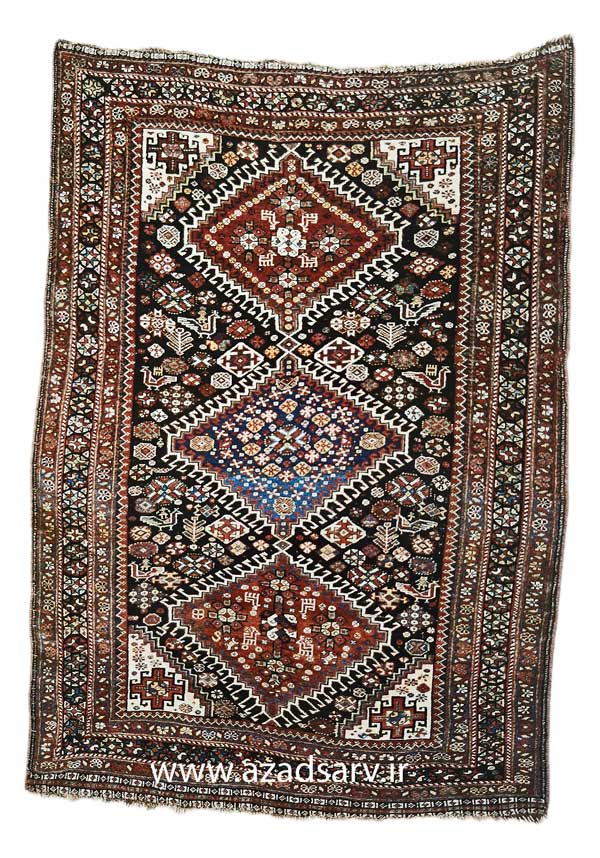

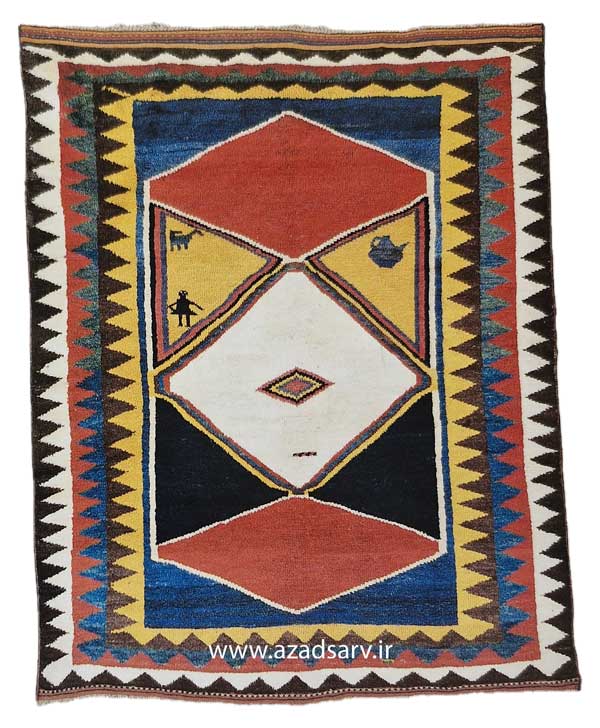

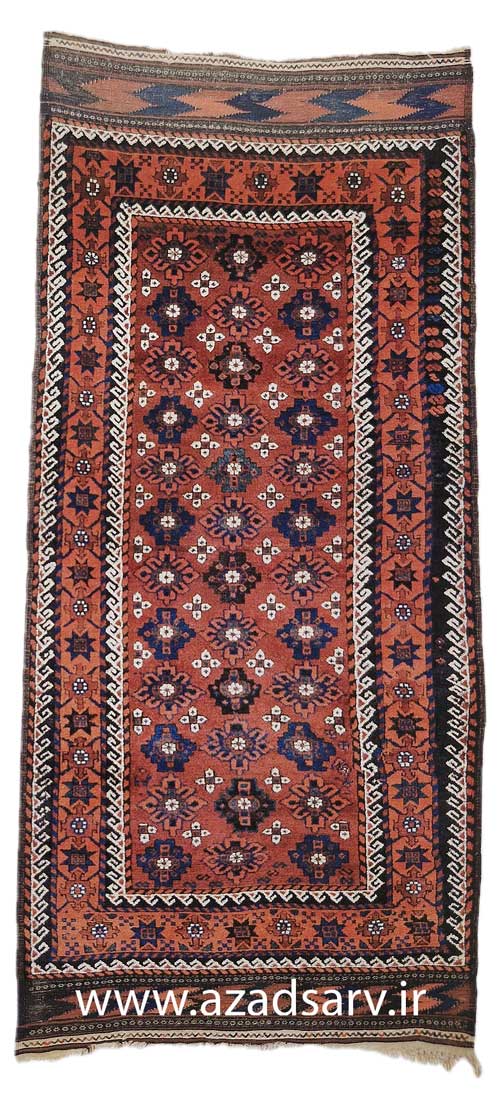

The Qashqa’i weave two types of rugs. Probably the most ancient tradition is the gabbeh rug. These have probably been woven for local use for centuries, and until recently have been ignored by collectors The rugs most frequently woven for the market are all of wool, asymmetrically knotted and are based primarily upon traditional Persian designs, with frequent use of the herati pattern, at times with a small medallion. The repeating boteh also occurs on many Qashqa’i rugs, and adaptations of the Moghul mille fleurs design in a prayer rug format are also woven but these are ordinarily made in the workshops of settled tribespeople around the town of Firuzabad rather than by nomads.

Qashqa’i rugs often show a variety of ornaments arranged with less formality than one would find on a Persian city rug, and they carry about them a liveliness often lacking in the typical village rug. Many nomadic rug enthusiasts see these pieces as adhering more to earlier and non-commercial traditions than the rugs of settled people, and yet that may be an exaggeration. The degree to which these rugs predate the expansion of the Persian rug industry in the late nineteenth century is still not clear, although a few have inwoven dates suggesting a mid-century origin. This brings up the question of whether the original Qashqa’i products are the gabbehs and kilims, while the asymmetrically knotted rugs in non-tribal designs may represent a later commercial production.

The best of these rugs are powerfully coloured and boldly designed, often showing additional simple geometric border stripes at both ends (Figures 28 and 29).

There has never been a large supply of the higher grade Qashqa’i rugs, and the best are avidly sought by collectors.

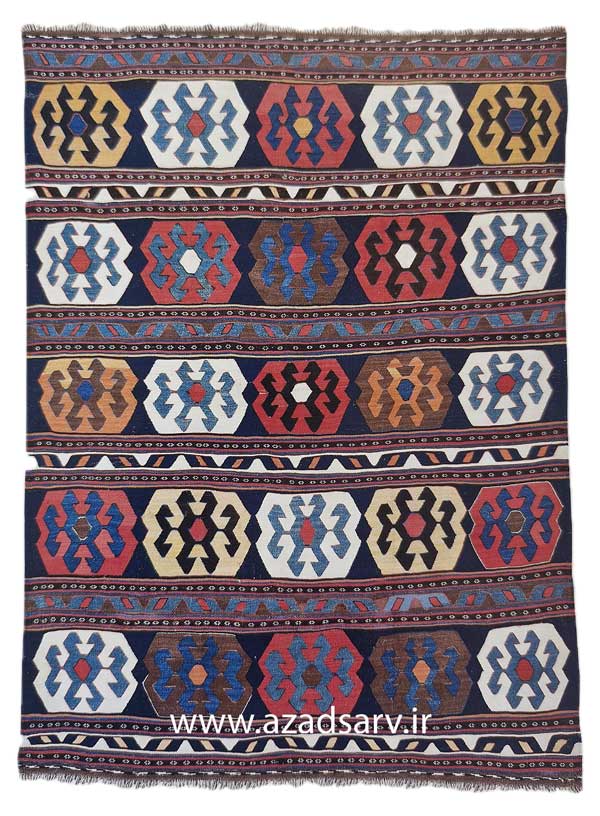

A number of trappings associated with nomadic life are also made by the Qashqa’i, including many kilims, horse covers, and a number of bags. Qashqa’i kilims in particular are woven in vivid colours that resemble more the gabbehs than the other Qashqa’i pile weaves (Figure 30)

The Khamseh Federation

This s grouping of tribes of diverse origins, including Arabs, native Iranian tribes such as the Lors, and Turkic groups not allied with the Qashqa’i. The Arab tribe includes a number of Arabic speaking peoples, some of whom claim to have migrated into Iran from the Arabian Peninsula at the time of the Islamic conquest in the seventh century. Turkic elements are found among the Baharlu and Ainalu, while a number of tribes have members of Lor descent. Not surprisingly rugs of these peoples cover a range of types, although they are often difficult to distinguish from each other and at times may resemble Qashqa’i rugs. One characteristic is that Khamseh rugs are more likely to show dark wool warps, while warps of Qashqa’i rugs are more commonly ivory. Khamseh rugs are also not so likely to be double-warped and are generally looser in construction.

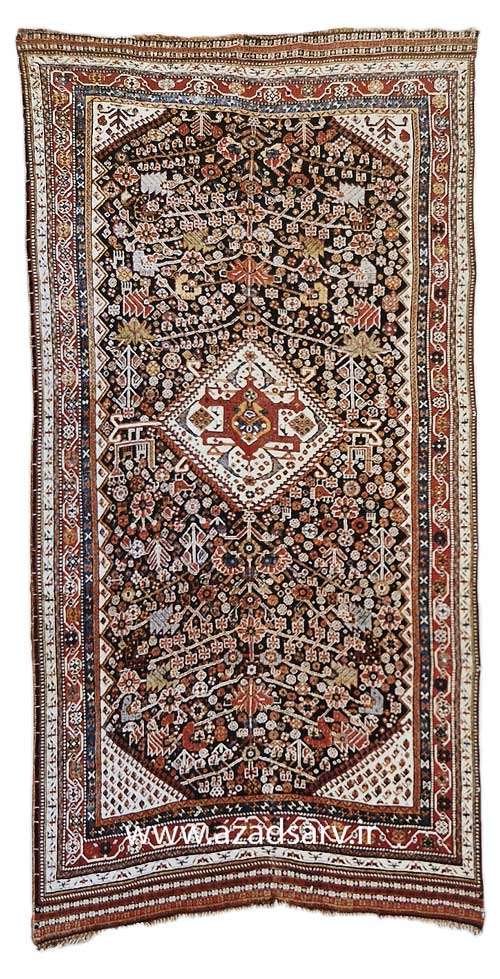

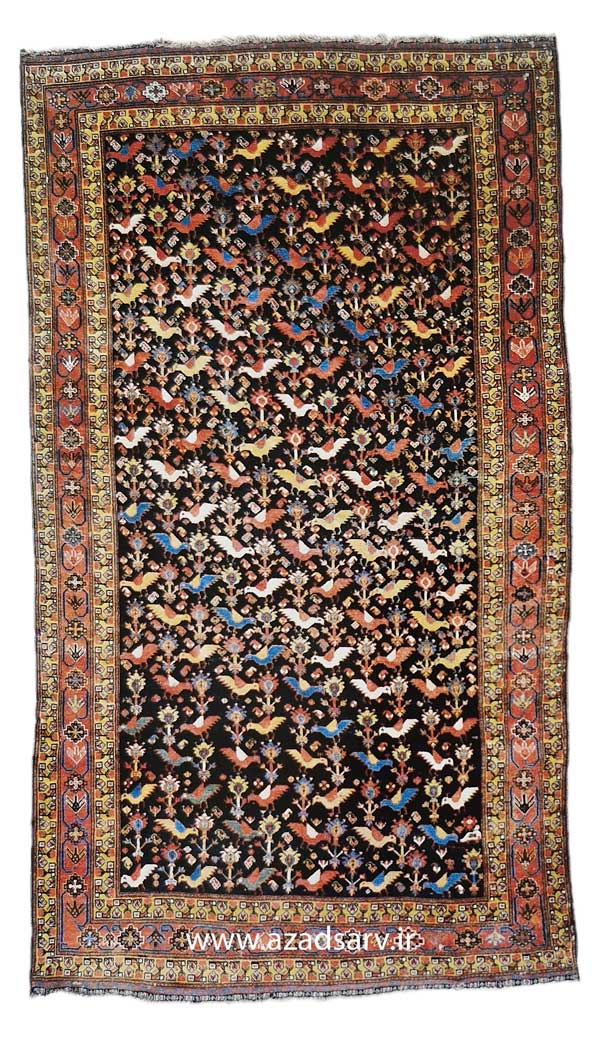

Earlier pieces may show great charm and excellent colours, although the colour scheme is often slightly more subdued than that found on Qashqa’i rugs. One often encounters a design in which stylised bird figures are repeated in different colours throughout the field (Figure 31).

There are some examples with three or more simple, lozenge-shaped medallions along the vertical axis (Figure 32). The rugs are variable in size, but seldom exceed about 6 x 12 feet (1.82 x 3.65 metres). Prayer rug designs are rare, but there are a few Pictorial ugs. Often one finds repeating geometric figures with relatively narrow borders.

Some rugs are identifiable as products of various Lori tribes. some of whom are affiliated with the Khamseh (Figure 33).

There are also some particularly colourful Lori gabbeh rugs which are difficult to distinguish from those of the Qashga’i (Figure 34).

The Khamseh Federation does not have the same kinds of historic traditions as the Qashqa’i, as 1t was formed only in the nineteenth century. Primarily it was assembled by external political forces attempting to form something of a counterweight to the powerful Qashqa’i. As the Khamseh Federation is made up of disparate elements, it has not maintained the same political clout as the Qashqa’i, and it appears to be diminishing in importance

Gabbeh rugs from the Shiraz area

In the late 1980s the Shiraz area was the centre of the natural dyeing revival that has had a great impact on the entire rug industry within Iran. As natural dyeing had essentially completely disappeared from Iran, it took several enterprising dyers to began experi- menting with such materials as madder, natural indigo, and yellow dyes from native plants. For reasons not entirely clear, many of the earliest rugs from this project were gabbehs with a relatively coarse weave and bold, simple designs

When these appeared at a major trade fair in Tehran in ۱۹۹۲, the results left a deep impact on many of the dealers in attendance, but there were still some needed adjustments. The reds seemed a little too sombre, and the yellows appeared to be the wrong quality. Within several years, however, the necessary adjustments had been made, and the naturally dyed gabbeh became e great commercial success. The gabbeh was originally associated with the nomadic way of life while the new production i 1S clearly aq commercial enterprise. As these gabbeh do not represent tribal rugs, the new production cannot be identified as either Qashqa’i or Khamseh, and has become more of regional a enterprise It has also been widely copied abroad, and one now finds Shiraz-type gabbeh rugs from Pakistan and India.

The Afshar

While village and nomadic rugs from rural parts of the province of Kerman are often described as products of the Afshar, there are a number of peoples living in this

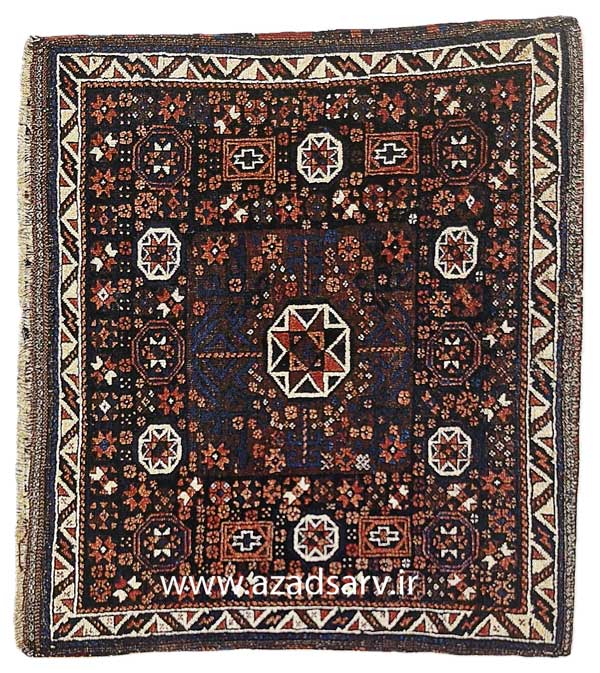

area, although weavings of specific groups are extremely difficult to distinguish. Those with symmetrical knots are said to have been woven by nomads of Turkic origin, while asymmetrically knotted rugs are attributed to villagers of Iranian descent, although no doubt there are exceptions. The rugs are usually small, although there are a small number of nineteenth century pieces made in adaptations of city designs.

The old ugs are all wool, while more recent examples have a cotton foundation. Some pieces have long flatwoven bands at both ends, as one finds on some Turkmen rugs. Many of the designs show stylised versions of city designs, with stiff medallions or botehs (Figures 35 and 36).

Some show repeating geometric figures. Field colour is often of blue, and many of the rugs show as much blue as red. A large number of bags are found from this area, as are flatweaves in a variety of structures

The Baluchi

The Baluchi live in eastern Iran, adjoining parts of western Afghanistan, as well as parts of Pakistan. They speak an Indo-Iranian language, and ordinarily inhabit the poorest parts of the three countries, living on their flocks of sheep and with probably a smaller settled component than either the nomads of the Shiraz or Kerman areas.

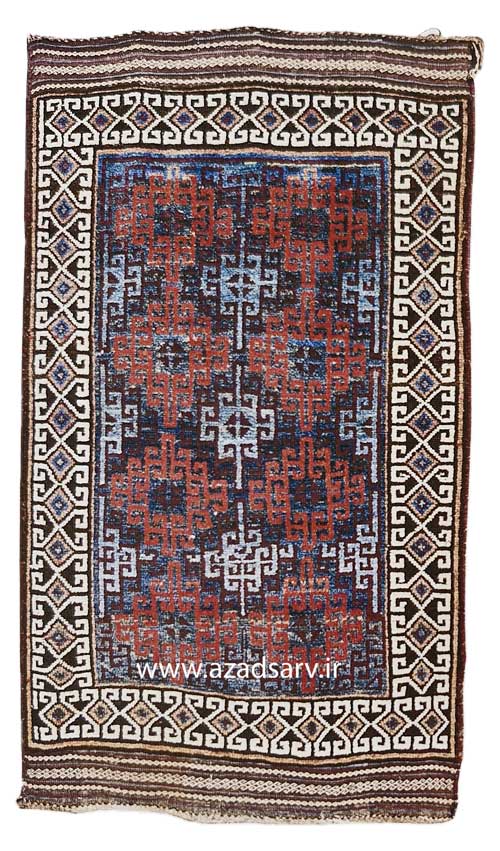

Baluchi rugs are the darkest group of Near Eastern pileweaves. They are asymmetrically knotted on a wool foundation and, except for a group of Baluchi rugs from north-western Afghanistan, are usually small. Rugs of the nomadic Baluchi usually show three or four bundle selvage of dark goat hair on the a sides and kilim ends that may be decorated with rows of weft float or other flatweave technique.

There are many Baluchi saddlebags, often larger than most found elsewhere, and the designs may consist of repeated geometric figures or stiffly-drawn bird figures. At some point there is usually a figure in ivory which stands out from darker colours (Figure ۳۷).

Pieces with prayer rug designs are common, usually with a squared mihrab and often showing a tree-of-life design or repeated geometric figures Baluchi rugs woven in and around the Iranian towns of Turbat-i-Heydari and Turbat-i-Jam are finer than most-others, and often show renditions of the herati or mina khani design (Figures 38 and 39).

Until the last part of the twentieth century Baluchi rugs were among the least expensive hand-knotted floor coverings, and they were often regarded as beneath the notice of the serious collector. This has dramatically changed, as a number of serious collections based on Baluchi rugs have been formed, and a wide literature on the type has accumulated What was formerly seen as small, sombre, loosely woven rugs, are now taken seriously, backed up as they are with a careful analysis of designs and iconography.

The Shahsevan and rugs of the Veramin area

The Shahsevan are a nomadic and semi-nomadic group scattered about eastern Azerbaijan, with some migrating as far south as the Hamadan Plain in winter. In the summer their pasturage is farther north, mostly on the Savalan Massif east of Tabriz. Their best known woven products are attractive bags in a fine soumak structure, although one may find less distinguished pile rugs in north Persian bazaars that are described as Shahsevan work. From time to time finely woven kilims are attributed to the Shahsevan. although the label at times seems to be assigned without hard information on origin

While there are some city-type rugs woven in Veramin, usually in the mina khani design, rugs with this label are often woven by nomadic groups who winter in the area around the city because of its relatively mild weather. These tribes include some Shahsevan, Lori, Kurds, and other groups, whose woven products includes a number of bags, animal trappings, and a type of kilim in ‘ eye dazzler’ designs, with a vivid interaction of strong colours (Figure 40). At_times the Veramin label seems to be loosely applied to small tribal pieces which cannot be more specifically identified.

**********************

Reference

ANTIQE ORIENTAL RUGS/ Murray Lee Eiland III